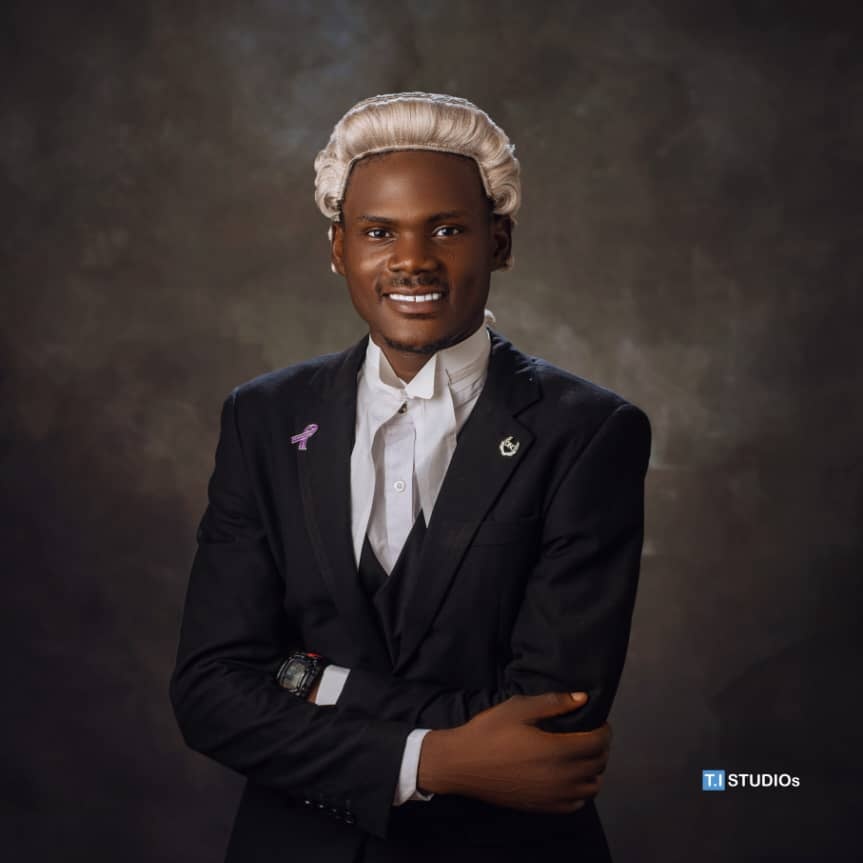

By P.L. Osakwe

■ Introduction

In the jurisprudence of Nigeria’s electoral law, time is not merely a procedural detail — it is the very soul of jurisdiction. Few principles are as consistently echoed in the decisions of our courts as the requirement that pre-election matters must be filed and determined within strict constitutional limits.

Section 285(9) of the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999 (as amended), stands as the sentinel guarding this boundary. It provides that:

“A pre-election matter shall be filed not later than 14 days from the date of the occurrence of the event, decision or action complained of in the suit.”

Section 285(9), Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria 1999 (as amended).

This seemingly simple provision has generated an extensive body of case law, clarifying that delay is not merely frowned upon, it is fatal.

The Constitutional Imperative of Time.

In WIKE v. CHINDA (2020) All FWLR (Pt. 1047) 35 at 64, para. C, the Court of Appeal reiterated the sacredness of time in electoral adjudication, holding that:

“Time is of the essence in every pre-election matter being peculiar and sui generis. As a general rule, where a party is guilty of undue delay in instituting a pre-election matter and pursuing same on appeal, the court will decline jurisdiction to hear and determine same.”

WIKE v. CHINDA (2020) All FWLR (Pt. 1047) 35 at 64, para. C (Court of Appeal)

This pronouncement captures two profound truths:

1. Pre-election cases are sui generis: that is, they stand in a class of their own, governed by specialized rules distinct from ordinary civil proceedings.

2. Time defines jurisdiction: once the constitutionally prescribed time has expired, the court is stripped of the power to entertain the suit, no matter how meritorious the claim may be.

The message is unmistakable: in electoral disputes, even the most righteous cause will perish at the altar of time if not brought promptly.

The Jurisprudence of Delay.

The Supreme Court reinforced this principle in GWEDE v. INEC (2015) All FWLR (Pt. 767) 615 at 656, paras. C–D, when it held that:

“It has been held by this court that in an election or related matter, such as pre-election matter, time is of the essence, and that as a general rule, where a party is guilty of undue delay in instituting a pre-election matter in the High Court, particularly after the conduct of the election in issue, the court will decline jurisdiction to hear and determine same.”

GWEDE v. INEC & ORS (2015) All FWLR (Pt. 767) 615 at 656, paras. C–D (Supreme Court)

Here, the apex court emphasized that the law frowns particularly on litigants who sleep on their rights until after elections have been conducted. By that time, the legal landscape has shifted, what was once a pre-election issue metamorphoses into a post-election one, and the appropriate forum becomes the Election Tribunal, not the High Court.

Thus, the failure to act within time not only bars access to the court but may also change the very nature of the case.

The Administrative Nature of INEC’s Actions.

Still in GWEDE v. INEC (supra) at page 647, paras. B–C, the court clarified an often-misunderstood aspect of pre-election disputes:

“This court has held that publication of the list of candidates to contest an election by INEC (1st respondent) is an administrative act which does not confer or take away validity from a duly nominated or substituted candidate.”

GWEDE v. INEC & ORS (2015) All FWLR (Pt. 767) 615 at 647, paras. B–C

This distinction is significant. INEC’s publication of candidates’ names, while public and consequential, does not itself create or extinguish a candidate’s right. The act of nomination or substitution derives its validity from the internal processes of the political party and the law, not from INEC’s publication.

Therefore, a challenge to such publication must still comply with Section 285(9). The 14-day clock begins to tick from the date of the event or decision complained of — whether it be the party’s primary election, a substitution, or INEC’s publication — whichever directly affects the claimant’s legal interest.

■ Why is the Law Strict?

The rationale for this rigidity is rooted in public policy. Elections are time-bound processes. The entire democratic machinery depends on predictability and finality. Allowing pre-election litigation to drag indefinitely would paralyze governance and frustrate the electoral calendar.

Hence, the courts have consistently insisted that:

Time cannot be extended by consent or discretion, and

The limitation period under Section 285(9) is mandatory and jurisdictional.

No sympathy, however compelling, can rescue a case filed outside the constitutional window. As the Supreme Court has often remarked, equity aids the vigilant, not the indolent.

■ Conclusion.

The doctrine of timeliness under Section 285(9) CFRN is more than a technical rule, it is a constitutional command. A pre-election matter brought even one day late is as good as dead.

In WIKE v. CHINDA and GWEDE v. INEC, the courts reaffirmed that time governs not only when a litigant may approach the court but also whether the court may act at all.

For every aspirant, lawyer, or political actor, the lesson is clear: in the theatre of electoral law, delay is defeat, and promptness is power.

■ References

1. Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999 (as amended), Section 285(9).

2. WIKE v. CHINDA (2020) All FWLR (Pt. 1047) 35 at 64, para. C (CA).

3. GWEDE v. INEC & ORS (2015) All FWLR (Pt. 767) 615 at 647, 656, paras. B–D (SC).

4. See also OLOFU v. ITODO (2010) 18 NWLR (Pt. 1225) 545 (SC) — affirming that failure to comply with statutory time frames in election matters robs the court of jurisdiction.

5. ANPP v. GONI (2012) 7 NWLR (Pt. 1298) 147 (SC) — reaffirming that the limitation period in Section 285(9) is strict and mandatory.