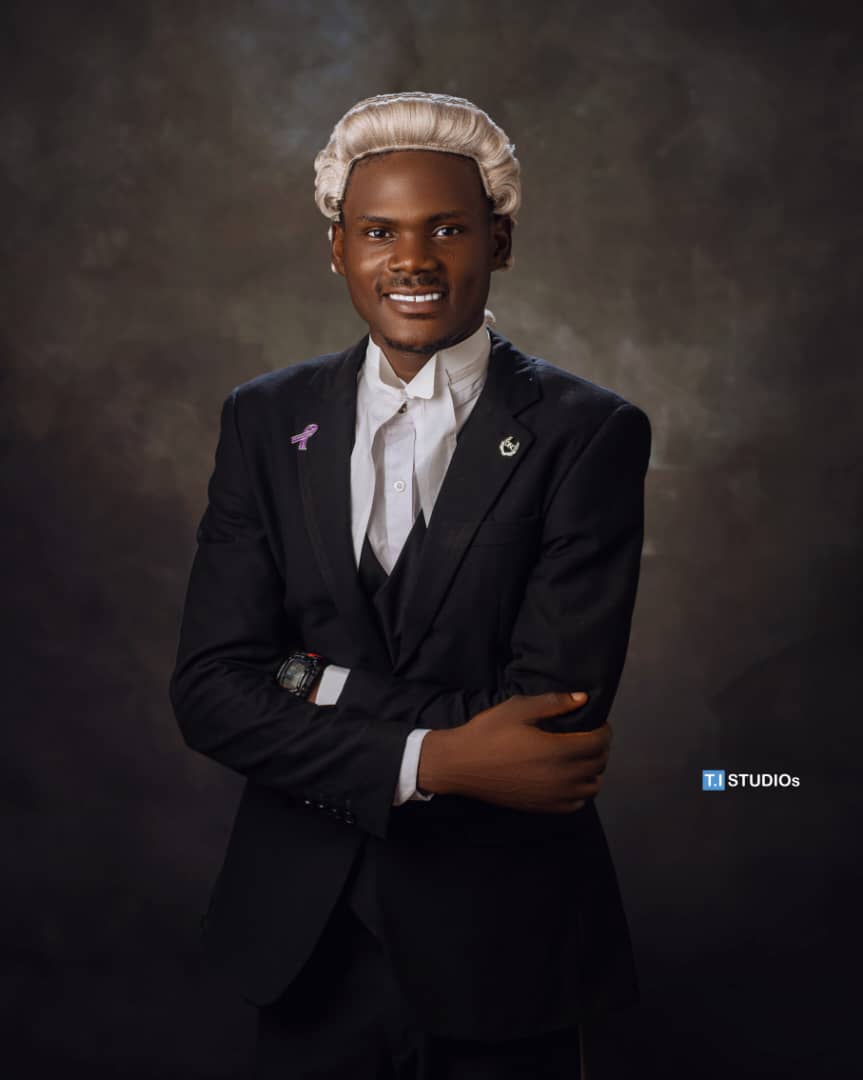

By P.L. Osakwe, Esq.

1. Introduction

In law, not every opinion counts, only those grounded in expertise, experience, and credibility. Courts often depend on experts to interpret complex facts, but the real question remains: who qualifies as an expert witness?

The Court of Appeal in AL-USABS VENTURES LTD & ANOR v. GUARANTY TRUST BANK PLC & ANOR (2021) LPELR-55789(CA) revisited this critical question, providing a contemporary interpretation of what constitutes “expertise” under Nigerian law.

2. Legal Foundation: Section 68 of the Evidence Act 2011.

The foundation for expert testimony in Nigeria lies in Section 68 of the Evidence Act, 2011, which provides that:

“When the Court has to form an opinion upon a point of foreign law, customary law, or science or art, or as to identity of handwriting or finger impressions, the opinions upon that point of persons specially skilled in such foreign law, customary law, or science or art, or in questions as to identity of handwriting or finger impressions, are relevant facts.”

This section recognizes the admissibility of expert opinion but leaves the determination of expertise to the discretion of the court.

3. Judicial Interpretation: The Test of Qualification.

In AL-USABS Ventures Ltd v. GTBank Plc, the Court of Appeal emphasized that:

“Evidence of opinion of an expert is relevant, but he must be called as a witness and must state his qualifications and satisfy the court that he is an expert on the subject in which he is to give his opinion, and he must state clearly the reasons for his opinion.”

at p. 60.

The Court further held that:

“While the above section of the Evidence Act states who an expert is, it does not provide any guidelines for ascertaining the expertise of a person held out as an expert. In practice, the court usually relies on evidence as to the educational or practical experience of the expert to ascribe probative value to his evidence.”

p. 60.

Thus, expertise is not presumed; it must be proven through academic qualification, professional training, or practical experience. The court must be satisfied, from evidence, that the witness possesses the requisite skill to aid its understanding of technical matters.

4. Reliability of Expert Evidence.

Qualification alone is not sufficient. The probative value of expert testimony depends on the soundness of the opinion and the factual basis on which it rests.

The Court held that:

“It is trite law that where evidence presented to a court is predicated on the opinion of an expert, the factual basis of the opinion must be presented to the court and it must be complete, real and genuine; an opinion of an expert which is based on doubtful grounds, incomplete facts or unrealistic assumptions cannot be relied upon by a court.”

p. 62.

Therefore, an expert’s role is to assist the court, not to substitute the judge’s evaluation. The court remains the ultimate decider of fact and law.

5. Comparative Insight: Evidence of a Child Witness.

The importance of competence and credibility is also evident in AYUBA v. STATE (2021) LPELR-56550(CA), where the Court addressed the admissibility of evidence from a child witness under 14 years.

Relying on Section 209 of the Evidence Act 2011, the Court stated:

“In any proceedings in which a child who has not attained the age of fourteen years is tendered as a witness, such a child shall not be sworn and shall give evidence otherwise than on oath or affirmation, if in the opinion of the court he is possessed of sufficient intelligence to justify the reception of his evidence and understands the duty of speaking the truth.” at p. 29.

However, such testimony must be corroborated by other material evidence before a conviction can be sustained:

“A person shall not be liable to be convicted for the offence unless testimony admitted by virtue of subsection (1) of this section and given on behalf of the prosecution is corroborated by some other material evidence in support of such testimony implicating the defendant.” p. 29.

6. Shared Judicial Philosophy: Competence and Credibility.

Both cases reflect a consistent judicial philosophy, that credibility precedes admissibility. Whether it is the child whose mind must grasp truth, or the expert whose mind must grasp science, the court’s role is to ensure that only credible, competent evidence guides justice.

Thus, the standard for both is not merely ability to speak, but ability to assist the truth.

7. Conclusion: Expertise as Responsibility.

An expert witness is not an advocate in disguise; he is a servant of truth. His duty is to clarify, not to convince. As the Court of Appeal made clear, expertise is earned through learning and experience, and its testimony must be rooted in objectivity, completeness, and reliability.

In the same breath, a child witness, though innocent and untrained, must still pass the test of understanding and corroboration.

Ultimately, the integrity of justice depends on the integrity of evidence, and the integrity of evidence depends on the competence of those who give it.

● References

● Primary Legal Sources

1. Evidence Act, 2011 (Nigeria), Sections 68 and 209.

2. AL-USABS Ventures Ltd & Anor v. Guaranty Trust Bank Plc & Anor (2021) LPELR-55789(CA), per Nimpar, J.C.A., pp. 60–62.

3. Ayuba v. State (2021) LPELR-56550(CA), per Abiru, J.C.A., p. 29.

● Secondary Sources.

4. Aguda, T. A. (1980). Law and Practice Relating to Evidence in Nigeria. Ibadan: Spectrum Books.

5. Nwadialo, F. (1999). Modern Nigerian Law of Evidence. 2nd ed., University of Lagos Press.

6. Oputa, C.A. (1996). Judicial Responsibility and the Rule of Law in Nigeria. Lagos: Nigerian Institute of Advanced Legal Studies.

7. Agaba, J. K. (2019). Practical Approach to Evidence in Nigeria. Jos: Faithlink Consults.

8. Onnoghen, W.S.N. (2013). “Expert Evidence and the Court’s Discretion.” Nigerian Bar Journal, Vol. 8, No. 2.